If you enjoy this show and would like to help me spread the word about it, or support it financially, you can find out more at nuancespod.com/support

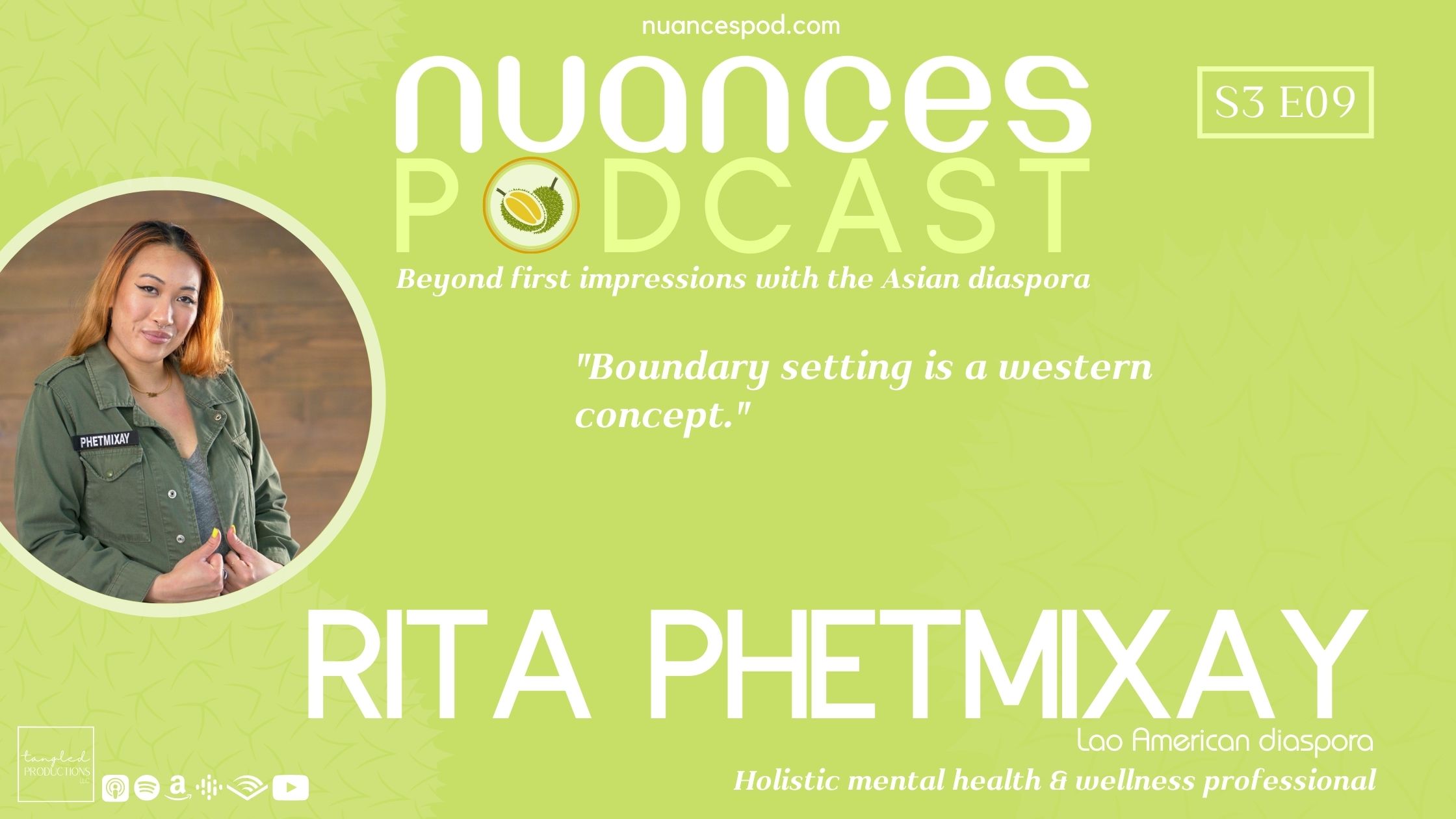

GUEST BIO

Rita is a 2nd generation Lao Isaan (pronounced E-sahn) American holistic mental health & wellness professional based in Los Angeles. She is also the creator/host of the Healing Out Lao’d podcast, which explores the intersections of Lao diaspora storytelling, healing, and tools for sustainability!.

Instagram | TikTok | Twitter | Facebook | Web

DEFINITIONS

- Pho: Vietnamese soup dish consisting of broth, rice noodles, herbs, and meat.

- Laos: Country in South East Asia bordered by Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, Myanmar & China

MENTIONED

- Lina V

- Laab (Vegan recipe)

- Laab Diip (Raw beef salad)

- Pho Lao

- Thum Mak Hoong (Lao Papaya Salad)

- S3 E03: Dr. Manijeh Moradian on covert CIA operations to overthrow governments

- Legacy of Wars Virtual Library

TAKEAWAYS

- Laos is the most bombed country per capita, and it was bombed by the US during its secret war on Laos and Cambodia at the same time as its war on Vietnam.

- Being able to name previous generations’ trauma responses, such as being overly protective, or overly frugal, and how they shaped our behavior patterns (eg. lack of agency/trust) can help us finally heal and stop the cycle of intergenerational trauma.

- Moving from a place where you’re the only Asian or only anything, to a place where you’re surrounded by your people can be jarring at first.

- In Asian cultures, setting boundaries can sometimes feel rigid. The way to soften these black and white definitions is to learn to communicate our love and desire to please, while still also communicating our own needs.

- While our culture was shaped by the people who created it and the norms at the time, we in the present have a chance to shape it for our current time.

- Patriotism is more nuanced than unconditional love for the country. For many, it comes with pride, joy, but also grief and a feeling of responsibility.

- Losing part of our identity is hard, but it can also bring a lot of growth as we expand how we define ourselves.

- It’s easy to blame other people or circumstances, but no matter what the situation is, we are ultimately responsible for managing our feelings, and setting healthy boundaries.

CONTACT

Instagram | TikTok | Web | LinkedIn | Twitter

Host: Lazou

Additional Music Links:

Nuances Podcast – curated Spotify | Apple Music playlists with past guests, hosts & more Asian diaspora artists.

SPONSOR

Featured song: “Until the Daylight Comes” by 23rd Hour

This episode is brought to you by 23rdhr.com.

Video with captions

Transcript

Lazou: Our guest today is Rita Phetmixay. Rita is a second generation Lao Isaan American holistic mental health and wellness professional based in Los Angeles. She’s also the creator and host of The Healing Out Laod podcast, which explores the intersection of the Lao diaspora, storytelling, healing, and tools for sustainability.

Rita, welcome to the show.

Rita: Thank you so much for having me. I’m excited to be here.

Lazou: You had a short film titled "Phetmixay Means Fighter". So tell us about your name and your relationship to it.

Rita: Yes . Phetmixay means Fighter. I created a short documentary film that highlights the nuance and the energy that my family brought to the United States. And so my dad was a rebel in the secret Civil War in Laos. He actually had to create an alias and change his name because the communist regime party was looking to kill him, my dad’s a fighter. It really resembled, just being able to overcome all odds, being resilient. I think that translated, in the energy that he had when he was all of us kids children of refugees in a foreign country.

And for me, this my relationship with my last name goes back to war times and being able to really fight through and find some level of liberation, freedom, be able to be your authentic self. The Lao people, we’ve always had to fight for resources, fight for representation.

And so for me, this is a lifelong journey of being able to embody that energy of resilience of fighting, of, again, resting as well. So part of what I fight for is rest. So that’s really what it represents for me.

Lazou: Yeah, that’s fascinating. I didn’t know about the fact that your dad changed his name. So that’s the name that he adopted.

Rita: Yeah, you know, Phet means diamond and Mixay means a winner, somebody who overcomes all odds. And so diamond you think about what it represents diamond in the rough, that phrase. And, no matter how hard you hit it you can’t really change the composition of it. It’s just really hard and so I think it’s the same dynamic that my dad saw in himself: I’m gonna win this war even if I go to another country and start a new life, I’m still a winner in myself and how much effort I’ve put in my family and how I’ve cultivated and raised my children to be the best of the best.

Lazou: Yeah. For many of us here, even though we’re all under the API umbrella, we don’t know much about Lao history or Lao culture. Do you wanna go a little bit more into Lao history and how your family ended up moving to the US through Thailand?

Rita: Yes. you know, I just wanna preface that, even a lot of Lao kids in the diaspora don’t even know a lot about their history and culture just by virtue of intergenerational trauma that has taken place in refugee parents who are really sensitive to reliving those traumatic memories of escapism, being displaced and whatnot.

So I had the privilege of learning my history through my dad’s lens, he’s a storyteller and he wanted to make sure that we knew our history. And so Laos is the country, about 7 million people. I’m pretty sure population has grown since the data on Wikipedia.

But yeah, there’s a secret civil war that took place in Laos and Laos was almost looped into the communist regime. So if you hear about the Vietnam War, it’s a misnomer because there’s other countries that were involved, not just Vietnam.

And so Laos was a proxy nation state that was involved. And at that time, around like 75, the fall of Saigon and communist regime taking over. Before that it was Royal Lao. So there’s like three kingdoms that evolved, over time, three monarchies.

And I don’t know the specifics, but I know that it was a clash of political ideologies that happened between the communist influence and then the royal monarchies. And then my dad was part of the royal monarchy side and trying to preserve freedom for his country.

And he was involved in war and combat and there’s a huge displacement during that time. The US involved themselves and that’s why a lot of people don’t know about Laos because there is a secrecy happening. Laos is actually the most bombed country per capita.

And of course that’s based off of some old data, maybe like the US is, doing this right now to some other country, who knows. But at that time, it was about nine years, maybe 64 to up until 75, there was just a long period of bombing from the US side to stop communism from infiltrating more of Laos and to preserve capitalism, for example.

And so that’s more like a the political view of Laos. But a lot of folks then, like hundreds of thousands of people, were displaced because of that war and the United States wanted to take responsibility of okay, if we lose this war, then we’re gonna receive your people who are part of the royal side.

And then there’s a huge displacement all over the world. So not only in the US but in Canada, in France in Australia, some in Germany, some New Zealand. We’re all displaced all over the world. But you know, think about the cultural side are very Sabai. Sabai it’s like a phrase that means like relaxed, really chill.

97% of population practices Theravada Buddhism. So really chill folks in general. And a lot of folks don’t know, again, because of that secrecy for that long amount of time. And there’s so many other types of tribes. So my tribe is the lowland Lao tribe. Then you know, hear of the Khmer folks, Hmong folks, over 160 different ethnic groups from Laos as well. So it’s hard to really clump into one particular type of identity or experiences when there’s so many different ethnic tribes So yeah, that’s know, Lao history from my point of view in a nutshell.

Lazou: Yeah, in another interview when you were talking about your film, you said that it was important for you to document and remember that history. Why was it important for you?

Rita: It’s important because if not now, then when? I suffered a lot from just not knowing. There was a lot of grief. Not seeing yourself on tv. Granted I had the privilege of learning about my history from my dad, but I imagine other refugee children who don’t see themselves, don’t hear these stories and are constantly experienced some level of violence or abuse or trauma, whether that’s with poverty, institutional racism, domestic violence in the household. But I wanted to give a different perspective: we are strong people, we have come from a path of resilience, and we don’t have to stop here and shrink ourselves and make ourselves smaller.

So I knew I had to do something with my dad’s story. And when I got to UCLA, I was a grad student in the Asian American studies program, and I was met with, you know, opportunity to create a short documentary film. And I took advantage of that because I can’t let this opportunity go to waste and I wanna see more of my people on the screen.

and I didn’t realize I had that talent to be able to translate, my dad’s story into film. That’s where it hits home. That representation is actually really powerful for our community that has been kept under the rug for so long.

Lazou: Yeah. I also don’t know much about my own family’s history. They escaped China. The only thing I know is that my grandfather disguised into a woman to get on a boat. Cause they didn’t wanna fight in that war. And they took a boat and went to Mauritius, which is where I grew up.

But I don’t know much of anything else.

Rita: What? Oh my gosh. That is wild. I love hearing about that history because I don’t even hear about that too. That you know Chinese migration and we don’t hear about that.

Lazou: so when, when you talk about, never seeing yourself represented, I can totally relate to that because as a Chinese Mauritian, which is, a tiny African island, I never see representation, yeah, I totally get that.

Rita: yeah, we have to put our people on the map. Come on, we exist. Because that’s the thing is that when we don’t see ourselves, it’s almost as if we have to live under a rock like we don’t exist. And that could be so painful to not know that, oh, there’s somebody else that relates or understands or even like y’all are real.

Cuz I also was isolated. I didn’t grow up with the Lao community. I grew up in a predominant white community back in North Carolina. We would go to the temple. But again, a lot of other Lao families were spread out all over, and we live in the rural side. So it was like, okay, I don’t get how we came here still, so who are these other Lao people, and it’s, it’s so important to build community and to recognize that, oh we are real. We’re not just existing in this delusion.

Lazou: Yeah, it’s interesting because it’s only now in my mid thirties that I’m starting to realize how much I believed that my voice didn’t matter for a very long time. And it’s only now that I’m starting to realize, hey, you know what? It should, why not?

Rita: Yeah, absolutely. If it’s not you, then who? Yeah. It’s like we can’t wait for someone else to say, oh, your voice matters. No, you already were born and just by virtue of being here and existing, your voice already matters. So that’s something I’ve had to learn and relearn. My dad he is been such an influential person in my life that he made us almost realize Hey, you know, like, like Lao people allow history, you’re gonna learn today. So I would say I have that privilege and it just pains me that my fellow Lao diaspora, children, refugees, don’t have that experience that I did. So I try my best to make sure that they know that they are worthy, they are seen, they’re validated.

And just because we’re not seeing each other in the mainstream, that we can create that in our own platforms. Because, again, social media is such a tool today to create massive movements and ideas and promoting different narratives. We’ve grown a lot since I have been raised and it just makes me humbled that my generation, millennials, have now created path for Gen Z. To be able to highlight and to know that yeah, it’s okay. It’s normal to be Lao. That just because someone doesn’t understand doesn’t mean it’s invalidated.

Lazou: Yeah, we talk about Lao not being represented and people just not knowing. So what are some of your favorite things about Lao culture that you’d like to share with our listeners?

Rita: Yes. I love our food.

Lazou: I’ve never had Lao food, so I’m very curious.

Rita: Yeah, your mind’s gonna be blown. Your taste buds are gonna be rocketing. It’s so good. And that’s something I knew I was gonna miss as soon as I graduated home. There’s a point in my life where I dealt with body image issues and I had this memory come up for me, I’m like, oh my God, there’s one point when trigger warning, but I stopped eating a little bit just because I had issues of being a little bigger in my eyes than the white skinny girls at my school. And then I realized why would I do that if, I’m growing up with such enriching foods I’m depriving myself of own people, my own foods.

And so I think for me, like that was a huge turning point where I had to recognize I am okay as I am. Our foods are so enriching, so fresh. I don’t know if you ever tried Laab L A A A B. Or P. But it’s minced meat salad. It’s made with fresh herbs, toasted rice, fish sauce, lime. That’s the national dish of Laos. Yes, it’s so good. So you can make it with, you know, duck meat, beef, chicken. You can have it raw beef. And depending on what your, preference is, that’s something you may see in Thai restaurants. But it’s actually the national dish of Laos.

And so grew with that. I actually grew up thinking that pho was Lao because again, I didn’t grow up in a Asian community. And so my parents particularly my mom cooked pho. And I grew up thinking pho was Lao It wasn’t until college that I realized oh like, Vietnamese people eat pho and they have their own type of pho and it just was again, mind blowing.

But again our food is all fresh. You can’t meal prep it. It’s a lot of stews, vegetables. Padaek is unfiltered fish sauce, that’s one of the main ingredients So it’s funky and fresh is how I like to describe it. One of my close friends he’s a Lao food influencer now, and he yeah, describes as funky, fresh, and I think that’s the most perfect way to describe our food. We like to invite people to gather together, to eat together because it tastes better when we’re in community together. So that’s one of the things I love about our culture and our people is that people are so giving so kind and being able to invite your fellow friend to eat with you just makes the experience so much better and the food taste so much better.

Lazou: Absolutely. Now, you grew up in the south in a predominantly white neighborhood. Did you feel tension between your Lao culture at home and the western culture everywhere else? How did you navigate that as a family?

Rita: Yes, so much tension with the white dominant culture, which is again, a lot of what I talk about today, on my platform. My dad, he, actually moved us from California to North Carolina and he was first like scoping all these different states in the south and found North Carolina to be quote unquote safest when it came down to where to raise children, because in Oakland there was a lot of gun violence, a lot of drug abuse that was happening. And he was like, oh, this is not a safe place physically to raise my children, but did not realize the level of racism that we would actually face.

So I grew up, again, predominantly white community. All the way up until I went to college. It really made me question myself, my identity. Why do I look the way I do? Why do I have these eyes? Why do we eat different food? Why are people making fun of my food saying that it stinks or smells funky?

Something that I love about our culture, my people and my family particularly, is that my parents just, bit their tongue and was like, all right, let’s just go to church and build community there. So we went to church and we went to the temple but my dad was still very grounded in who he was.

He was like, yeah, you know, I go to the church, but do I believe in Jesus? No. So that was something that, that I think I had to reconcile with. But my dad, he never forced us to believe in a particular religion or spirituality, which I appreciate it a lot. But I learned from him that it was important to be Lao.

In hindsight, it was really hard for my parents to see us also take on quote unquote American values and dress the way we do. Ever since I was young, I like to express myself being sexy and playing with makeup things like that. Something that my parents weren’t privy to per se. So there’s a lot of disagreements about that. I remember my dad saying one day at the dinner table, he was like, you need to be 75% Lao and 25% American. And I’m like, how do you even cut that up like a pie? when I think about it, it’s funny now, but I think I really had to grapple with how do I hold both identities and experiences with real value to myself and in my parents’ eyes to be accepted and validated by them.

Over time, ever since I moved to California, I’ve been in California, for about 10 years now I’ve had to shed and heal what those percentages mean and really understand how I am as Lao and proud as I can be. And I don’t mean to succumb myself to a percentage and I could freely just navigate who I am based off of my experiences that I’ve had.

But growing up it was a huge struggle to be Lao. I have to be like these white girls in order to be accepted. I had black and brown friends, but there was definitely anti-immigrant, anti-black sentiments up. It was really difficult to navigate as a young person who did not have a Lao mentor femtor themtor to be able to guide.

It was just us and our parents. Yeah, there’s definitely a lot of racial trauma that took place in North Carolina, but again, healing every day navigating these spaces and helping my community members really put a name to their experiences so that we all collectively heal and learn that there’s nothing wrong with who we are.

It was just the society that we grew up in that wasn’t okay with the other, the other being anything outside of whiteness or whatever the dominant culture is.

Lazou: It’s funny you say that your dad would go to church but doesn’t really believe in Jesus because all the Chinese Mauritians are both Buddhist and Catholic.

Yeah, they’re both

Rita: They’re like, why pick? right. That’s the thing. It’s we navigate spaces and we take on certain identities because we like this part of Buddhism. We like this part of Christianity.

Lazou: Yeah. It’s so you’ve been in LA for about 10 years now. What was that transition like from, North Carolina to LA was it a culture shock when you moved to la?

Rita: Yes, it was a huge culture shock and it was really uncomfortable for the first year. I felt like it was an out-of-body experience. Never been in a community where I’m not the only Asian. And at that time, I didn’t build a Lao community yet.

So I moved in 2013 to go to grad school. And I remember going to In N Out for the first time with a friend who lived in LA. And that was my first time that I saw a cop that was Asian and I was mind blown cuz that it does not exist in the south.

So I was so taken aback that I was like, oh my God, what is happening? This is another country. It is another world, it’s wild to me. But of course now I see more people of color in leadership positions and positions of power in LA and I had to really unlearn a lot of things that I was taught in terms of systems of oppression, white supremacy.

And I thought I knew everything when I was in college at university of North Carolina Chapel Hill, because I did start a sorority that was focused on promoting more diversity issues, social justice issues, advocating against social injustice, things like that. And I thought I was good.

And then I come to LA and especially in the spaces that I was, in Asian American studies, a lot of Asian AM organizing spaces, I was like, whoa, they’re taking it to another notch. And I was like, oh my gosh, I thought I was done learning.

And then I was yeah, caught off guard, but it really challenged me to do better and I actually healed a lot of my childhood wounds, racial trauma when I came to LA and then I didn’t realize that people can be so lovely. And I felt like a different sense of belonging as long as I was open to accepting it.

And I think a part of me wasn’t ready to let go of my old self, my identity of being the only Asian, I think I took pride in that for a certain time in my life. Because it gave me some level of validation and then I was like, oh my God, I’m not gonna be anybody in a sea of Asian when actually, no, this is building solidarity across different API groups and I’m getting more language and empowerment and being able to heal with a p I leaders who are also healing or mental health practitioners.

And finally being able to accept that helped me grow and do what I do, in the work of healing out Laod today. So in short, it was cuz I had to confront some really harsh truth and poor self image of my old self. But now that I did that, there’s like freedom on the other side of oh I don’t have to live in fear of having to be only recognized for my Lao or Asian identity, that I have a voice beyond that, I have a voice beyond my trauma.

And so it’s been an incredibly healing journey to have transitioned and reasons why I stayed here for so long and been with my community here because there’s a different level of trust, different level of connection that I feel with the people here.

Lazou: Yeah, it’s interesting how our identity is often defined by the way people perceive us. for you, you were the only Asian kid, so that became part of your identity. I’ve had similar, experiences where I had trouble letting go of something that I thought was a core of my identity and then I realized no, it’s just one of the things I am,

Rita: that’s the key is just acknowledging that we exist on a whole entire spectrum of so many different intersectional identities and that I don’t have to be simplified to being Asian or being Lao just because somebody else sees me as their only Asian friend.

Even at U N C I joined a predominantly Latina sorority. And growing up I was only in predominantly white spaces. And so coming to a community that was mainly Asian faces, I had to confront that I am more than that, and I don’t have to be simplified and I don’t need to be. Yeah. Like it’s just come on now. There’s so many other great things about myself.

Lazou: Yeah. So much of your work is centered around healing. Was your move to LA the point where you realized that you needed to heal?

Rita: That’s a good question. And no, I think maybe at the time it was just unconscious. I knew I needed to get out of North Carolina though, because at that point I believe that I outgrew my friends there, my professional journey there. And again, I moved because of the U C L A Asian-American Studies program. I thought I actually was going to do a pipeline to PhD by going to get my master’s first.

And what I initially wanted to do was to do research to inform policy practice on how do we get more Lao Americans into higher ed spaces because I experienced so much liberation in higher ed. I got to go places, I got to meet people and network and have all these different opportunities that I didn’t have when I was in high school in North Carolina. So for me it was almost like a safe container to be able to have a community set for me already in la. But meeting one of my big sis and mentors who was also in the Asian American Studies program and MSw program. She was really the entry point to a lot of the healing that I did for myself and being able to hold space and help me recognize what I went through wasn’t okay, because I think I was just on autopilot. I wasn’t open to confronting difficult emotions.

And she was one of the first people, Wanda she’s featured on my podcast and she’s been such a incredible light in my life that really helped me pivot and understand okay, what I went through wasn’t okay, and then start all of the feelings and all of the whatever I suppressed.

And so just, I think it just organically happened like by the virtue of the people I met here that was like, wow, we’re opening spaces up or all of these new emotions. I’m able to now feel that I don’t have to numb or suppress. And then um, came my period of being angry. I was so angry in grad school and I’m laughing about now because I’m like, wow, like that was wild, and then I realized oh, I don’t need to be angry as much anymore.

Of course, I have a right to be angry about if things don’t feel okay for me. But now it’s more regulated. For me to understand where I could channel that anger, I have to make space for that narrative too, because again, part of the healing journey is being able to feel all of these difficult emotions that I wasn’t able to prior to coming to la.

Lazou: Yeah, and since then you have become a licensed therapist So I would love to hear a bit more about that experience in terms of why you went into it and how as a Lao therapist you approach the healing process.

Rita: Yeah. By virtue of the people I met in LA especially Wanda man, I thought I was gonna just researched, informed policy practice. I was into programming. I wasn’t into like more macro social work and what that consists of, it’s more community organizing or, putting on programs and, being able to create a systemic change more so than the one-on-one.

But I didn’t realize that after gaining these skills and practicing these coping skills on my own, when it comes to emotional regulation and addressing different symptoms of distress and trauma. It took me, I believe, three years after graduating with my M S W to recognize that there’s a lot of power in being able to just finish up and get licensed.

And something that I think I wasn’t ready to accept because I thought the only pathway was to just do macro work, but there’s so many opportunities that come with licensure and yes you don’t have to have a licensure to do the work that you do in healing. There’s so many different ways to practice healing today.

You can do, you know, embodied coaching or yoga or, meditation or resilience coaching. There’s so many other ways to practice the work. But since I was already on that pathway, Wanda reminded me you know, you’re already 85% there. Why don’t you just take the next step?

So then I, my ass off and started actually getting my hours in for licensure in 2020 with the onset of Covid. And I was a covid therapist. a therapist practicing during the onset of the pandemic with a frantic population. And, not that I haven’t practiced before, but it was almost as okay, buckle down Rita.

and I haven’t seen this in my generation either. And I realized that, there’s so many people that required this space and, I finally understood what my purpose was to become this healing practitioner. And it would be a waste if, I worked all the way up here and wasn’t able to share my talents or my skillset and really hone into the collective healing space through a one-on-one experience. And so the one-on-one informs the collective, the collective informs the one-on-one. So I think for me, what my people were waiting for was just someone to just name it, that we need to heal. And so that’s where I put all of my experiences, my Asian-American studies background, my social work background, all into one mix where my people can see that, oh, it is possible to heal.

That we’re not just victims of war, or victims of domestic violence or trauma from the war experience of our parents. That we can really take charge of our life because I was able to demonstrate that for myself, obviously I can’t do this work if I’m not practicing it for me.

And I realized like I was sharing earlier about that time period when I was super angry, I was angry at my parents. I was angry at the white people. I was angry about systems of oppression. I was just so angry and it was uncontained. And until I was able to really hone in, I like, why am I so angry right now? And I was tired. I’m kinda tired of being angry all the time. And I was like, oh, okay. That’s not my natural state. My natural state is this is laughing, cutting up playful but we need a safe space to be able to do that in as well. And what’s safe for me is gonna be different to you.

After being able to navigate those tough emotions, I realized okay, what does it look like, for me to teach that is the next step. And so getting licensed, being able to teach other people and then create healing out Laod set the parameter and the bar for us to challenge ourselves to see us beyond just victims in this world, that we can take charge of our lives.

Lazou: Yeah. One of the terms that we hear a lot is intergenerational trauma. Can you tell us what that means?

Rita: How I define it is trauma that hasn’t been healed from the prior generation. Whether that is intergenerational poverty, whether that is domestic violence, whether that’s behaviorally. So if you grew up with a household where your parents were super anxious and controlled your every move, and you as a child, internalized that, oh, I don’t have agency.

And you then can pick up, those behaviors in your adult relationships and act people pleasing because you’re not sure of yourself, you’re not confident in decisions that you’re making. So I would say that is a product of intergenerational trauma: lack of confidence, low self-esteem, but again, stemming all the way from war trauma.

And, that’s what I witnessed in my own history of my parents navigating poverty, navigating the welfare system to a degree that they had to focus on how to survive. And because they’re focused on her survive, the emotional neglect was there. And we’re not blaming them.

We’re just noticing that, oh, okay, this is just what happened. They did the best that they could and the emotional connection, the attunement was just not there. So naturally as kids, for me, growing up and not being confident in who I am and acting codependent behaviors and having to heal that was really tough to recognize that I can survive, this decision I’m making and I have to be okay with that.

Lazou: Yeah. what do you advise clients who are suffering from consequences of intergenerational trauma? And they wish that the people around them who are inflicting those things on them would go to therapy, but they won’t

Rita: It’s so easy to blame other people for your misery and I think as adult children of refugees or immigrants, particularly from this experience, I think there’s a lot of liberation and taking personal responsibility. And we’re not saying that the perpetrator isn’t in the wrong or, that our issues are in a vacuum.

But for me, my experience of taking charge, of being able to have a healthy space of like what my parents did had nothing to do with me and my self worth and had everything to do with the circumstances they were in. So when I start to have that level of separation and space, I now understand my behaviors are a product of how they treated me, but now as an adult, I take responsibility for my feelings, my actions, my behaviors, and go to therapy. Yeah. For myself, process what you need to process. It’s gonna be unique and different for everyone. Everyone’s journey is different. But one thing I do want to acknowledge especially folks who have suffered from international trauma, is being able to recognize that it’s important to be able to welcome a lot of compassion for yourself and to acknowledge, you know, when there is judgment where there’s judgment.

There’s probably some level of shame as if you know you’re a bad child or you know you’re a bad person. If we can just recognize those thought process, that’s the start of being able to see oh, actually that’s not true. I’m not saying it’s a hundred percent not true, but maybe it’s 50%, maybe it’s 40%.

But if we can just be able to recognize that what we believe happens on a spectrum and that we can acknowledge those thoughts that are coming through, we can then shift it into something that feels a little bit more validating. So I would say start there and acknowledge that yes things happen and you don’t have to be a victim to what happened to you anymore.

Lazou: Yeah. If you could heal the whole diaspora, what would that look like?

Rita: Lemme just say I’m not God, but I don’t like to think of healing as a stopping point. I think it’s a continuum and that’s how I like to define it. It’s an ongoing process until your very last breath and just when you think you’re healed, then you know, something else happens. You’re like, whoa, I just flashed back into that moment in time when I thought I was over it and I’m not. And so let’s say like a diaspora that is healing is one that’s coming together. Being a community, laughing, being playful, and really being able to story tell being able to affirm each other and helping each other grow where there’s less gossip and more community building and being able to just recognize each other’s strengths and helping build each other up.

Yeah, I would say that’s what I imagine and hope for my Lao diaspora to continue to do.

Lazou: Yeah. That’s awesome. One of the common themes I’ve seen on this podcast is a lot of people go to a white therapist and they have a terrible experience.

I would love to hear your perspective as a therapist on how western approaches to therapy might be maybe not suited for Asian culture or how it might need to be adapted to account for cultural differences. Have you seen that in your work?

Rita: Oh, absolutely. I can pull out an example of boundary setting. So boundary setting is a westernized concept. There’s no such thing as boundaries in Asian culture, even Lao culture. I remember when you get mail sent to you and then your parents already have read it and ripped it up and then they give it to you like, Hey, you got mail?

I’m like, why is it open? And so I just remember those specific memories as a high schooler when I started getting mail. But I would say, as a clinician, Asian, Lao therapist something I have to acknowledge for my clients how hard it is to set boundaries.

Because boundaries can seemingly feel like you’re taking something away from somebody you’re withholding resources from, for example, your parents or elders who, all they do is want to help and support. And so we have to acknowledge that, maybe it’s not boundary setting, but maybe it’s how do we communicate the love that is still there and still instilling the boundaries of Hey, I wanna support you. I wanna be here for you. I wanna take this call. But right now, I’m busy. So I would say that’s such a important nuance, you know, as we’re talking about nuances, to be able to capture that boundaries can feel rigid in Asian culture where you either, are for me or you’re against me.

If you don’t give me resources, then you hate me. And it’s not so black and white. So we have to just make sure to be able to name that particular struggle is that it’s hard. And even me sometimes I still struggle with boundary setting, but having to practice this and teach my clients, this is something that we have to just learn that, as people who are in the intersection of Asian cultures or, particularly my experience Lao culture, and then American cultural values.

There’s that clash and we are just navigating the best that we can. And one doesn’t cancel the other out.

Lazou: Yeah, and that’s another thing I wanted to touch on is how our identity and our culture are so intertwined sometimes that it’s hard to let go of one without feeling like we lose the other. A lot of Asian cultures have problematic norms. Like very rigid gender norms or very sexist norms, this idea that you can’t question elders, whether they do something that you would disapprove of or not. So how do you approach letting go of these harmful beliefs? I know you talked a little bit about that on your social media, about letting go of the things that don’t serve you anymore while still retaining your cultural identity.

Rita: That’s the thing is that culture is not rigid. There’s so much that we could say that Lao culture is and what it isn’t. But I think the main thing is being able to recognize when you’re communicating, what is your intention. For example, I was learning from another client about how Christianity is sometimes used as a way to get a particular need met, for example oh, this person, they’re not Christian, so they may not have this set of values of love and whatnot. But again Christianity, there’s like millions and billions of people who are Christian. Same thing here, millions of people who practice Buddhism. And there’s just so many ways to see your culture being enacted and to not use that as a way to harm other people.

And harm is also very nuanced, right? Cuz you know how one person reads the way that you enact this exchange with them can be very different than the next person. And so for me being able to stand up for yourself and being able to hold the nuance of I’m a Lao woman. In Buddhist culture, you can’t touch the monk’s head. But for some reason, men can do that. And not saying I have to go and touch the monk’s head, cuz it’s like sign of disrespect and whatnot.

But there’s something there. You have to think about how was this even socialized? Who created this? And so what we are taught is actually what was the dominant culture during that time.

And if it was men who created it, then of course they’re gonna have that cultural value of women being less than, or women not being able to do this, or even, respecting your elders. It’s like, how are we using that? And we can respect the wisdom, we can respect, the experiences that the elders bring, but also how do we hold accountability of elders to be able to enact a model of healthy wellbeing, a model of support, a model of taking care of each other. Just because they’re elders doesn’t mean they haven’t, committed any harm, right?

So we’re not seeing terms, just black and white. We’re able to say okay, I hold you in high regard and I hold your wisdom and you’re also human. And I’m also human. Yeah. And just because I’m a practitioner and a healer or a mental health person, that doesn’t mean that I also don’t go through my own struggles.

And so I think it’s holding this dialectic of both and there’s so many different truths. How we navigate the cultural experiences. Are we using it to keep or are we using it to actually ensure safety? Like What are we doing with that information?

Lazou: One of the topics you mentioned you’d like to touch on is processing grief. What have you learned about grief through your work as a therapist?

Rita: Grief is heavy and needs to be processed. And what I learned about grief through my work, is it shows up in so many different emotions. Grief can look like shock. It can look like denial, it can look like anger, and it could finally look like acceptance. And what I learned is that there’s a sense of loss And that sense of loss is almost like a loss of your old self and a relationship to not even people. It could be with animals, it could be your relationship to your job. It could be relationship to a movie character or, substance issue, in community.

So It can be a very sensitive topic, but it’s important that we hold space for it and not just glide over it. Because it can be the reason why it’s hard to see the light at the end of the tunnel because there’s so much to be shared about the sense of loss and loss of oneself.

Lazou: Yeah. I think one thing that a lot of people struggle with is knowing what to say when people are going through grief. Do you have any tips on what to say that is helpful instead of hurtful?

I think there’s a lot of awkwardness when somebody you know is going through grief and you don’t know if what you’re going to say is gonna be helpful or if it’s going to just make them feel even worse.

Rita: I think it’s really uncomfortable just to feel grief in general, especially someone outside of you that’s bringing in their grief to your world. It’s uncomfortable. So a lot of times people may go into problem solving or trying to fix or advise the other person on how to move forward when it’s not their call when a person is ready to move forward.

So I think what’s important is, just acknowledge for yourself. Are you in a space, like a mental and emotional space to hold grief? And if you’re not in that mental and emotional space, it’s okay to have a healthy boundary. Because you may cause more harm than help. And if you are in that space to be able to hold, that grief with your friend or family member, then I would challenge you to be able to just listen.

We’re not offering any advice. We’re not trying to assume what the other person is thinking of or just being able to share like, Hey, you know what? That sounds really tough. Share with me, what’s going on and would it be helpful for me to affirm you right now? Would it be helpful for me to get you a glass of water or some food right now?

Do you wanna watch TV together? You just wanna be in community together. And so it’s really just tapping into the emotion and being able to attune to this other person. So these are like, some one-on-one therapeutic skills that I’ve had to learn too. As somebody who has benefited from somebody holding space and processing grief. So it really boils down to active listening skills.

Lazou: great advice. Now, one of the things I want to do in this new season of the podcast is reclaim what it means to be proudly American, or what American values are. So do you have mixed feelings about being American or are you proudly American?

Rita: You know, I’ve learned to have mixed feelings about everything.

Lazou: Fair enough.

Rita: a hundred percent. I’m like, dang, I don’t, I even feel about being Lao. But then I’m like, you know what? It’s fine. I am very Lao and proud and that’s one thing people will recognize about me is like, Rita, you’re just proud. Even like my students when I worked at ucla, a lot of them who are based in California have never been the South, but they’re like, Rita, I I love how you’re just proud to be from the south, even with the nuances of it being a racist, geographic location and whatnot. And, I just love that you’re just so proud. And so I think my pride it comes from Not being represented, you know, in certain spaces.

And so when I’m in LA I’m like, yeah, I’m from the south, But I think in terms of being American, I am proudly American, but there is that nuance of American capitalism that I’m not… again I don’t like to take that on, it’s uncomfortable. But at the same time, I benefit from being an American. There’s a lot of power, but also what do I do with that power? Yeah. What do I do with the stories that I hold, with social media platforms, and being a part of the diaspora even in Hollywood. Yeah. Living in LA there’s access to entertainment and whatnot. So with my American identity there comes grief and that grief of oh my gosh, the black and brown indigenous people that were murdered in order for this nation state to be built.

Yeah. So there’s that notion that I do reject where it’s that’s not okay, you know, but at the same time, it’s like over years of evolution how do we still be in touch with the present moment while recognizing that harmful past, and that violent past, and be able to recognize that my parents have been able to access resources through this American system.

They’ve been able to access resources. I’ve been able to benefit off of my brother being in the military, and I have to say that and own it. So I would say that, even in North Carolina um, because there wasn’t a huge Asian population, I never identified with Asian American per se until it came to SoCal and then I recognized that, oh, I’m not just Lao, I’m Lao American.

There’s this nuance because Lao people on Lao, they don’t say they’re Lao American. you know, I have to acknowledge that experience too and be okay with that. And, I’m okay with being in the mixed feelings.

Lazou: Yeah. Can you recall a particular memory of when you felt proudly American.

Rita: Yeah. I love that question. Cause it’s so funny. I’m like, when did I feel proud? I think I would say when my brother got into the United States Air Force Academy with what I knew back then, how proud I was to be an American, because that meant access to different opportunities and resources that my family would not have normally gotten.

A lot of people don’t know this about me, but I actually was gonna go to the Air Force Academy. It was either UNC or the Air Force Academy. And I chose UNC because I felt more connected to the campus, and I didn’t realize that the Air Force Academy was what my brother and my dad wanted.

But I would say when I saw my brother get into the Air Force Academy, it was like a ticket, to freedom for our family when it comes to financial access.

Lazou: Yeah, the phrase American values evokes very different things for very different people. So I would like to know what you consider or would like to consider American values.

Rita: American values.

Lazou: Not what other people think American values are, but what you believe American values should be.

Rita: Oh, and you know, I think free will, we hear about freedom of speech, but who actually has freedom of speech, you know? I think about like created for, white folks you know, with the whole pilgrimage and whatnot, all the way to that history.

one thing I do appreciate coming here, we probably couldn’t say the same things that we say here in Laos. There is that level of nuance to highlight that if I were to wear the old monarchy flag, I would probably be persecuted.

You cannot do that. But here in the United States, people can proudly experience expressing themselves in, whatever fashion or form and speak against a presidency but again, holding space, for people who have negative consequences of speaking up, like people losing their jobs, for example, for holding a different political ideology than their supervisor or management, that still happens.

I wanna make sure that we highlight, but I would say overall in the context that, we can be able to say what we wanna say without having like intense repercussions for that. But again that’s a nuance that I would say it’s different per person. But my experience has been pretty pretty good.

Lazou: Yeah, and I think that’s an important nuance to highlight because it’s very easy for americans to feel like we don’t have freedom of speech anymore. We don’t have these rights anymore. We are losing rights, literally, but like literally losing rights.

But are places where what we can do here is so much more than what is allowed there. And that is a privilege that we have and we need to use it.

Rita: Yeah. And to not abandon, that privilege either. Because. Again it’s so easy just to see from your experience than to see somebody who’s living in other countries where they’re constantly being persecuted for even wearing something different or, freedom of speech. having banned social media because a war was happening. Censorship is definitely an issue that is evolving as an issue, over time, but at the same time, it’s like just to recognize that things aren’t so black and white.

Lazou: Yeah, for sure. All right. So we like to end the interview with a rapid fire section. questions that are one word or one phrase answers. You don’t have to explain, but you can if you want to.

Rita: Okay, I’m ready.

Lazou: What’s an Asian food that you should like, but don’t

Rita: uh Durian,

Lazou: Fair enough? What’s an Asian food that you’ll never get tired of?

Rita: Chicken curry.

Lazou: a favorite Lao artist of yours?

Rita: Oh one of my close sister friends Lina V she has an incredible voice and is amazing performer, so she mixes a lot of modern Lao and then, R&B into her mixes. So she’s a very amazing artist in the Lao community. I hope that she gets the shine she deserves.

Lazou: Awesome. And what is your favorite representation of Lao culture you’ve seen on media.

Rita: I am really proud of the Lao food influencers that have promoted the Lao food movement, and they’ve been able to again use food as a catalyst to promoting not only our food, but you know, our people and have made our people more recognized as a part of that endeavor.

Lazou: And finally, what’s your favorite mental health or boundary setting hack?

Rita: Mental health hack. I love that. I would say more sleep. I just think that, as time goes by, you’re getting older that everyone can just use more sleep. So yeah, get more sleep to improve your mood.

Lazou: Awesome. Thank you so much for spending the time with us today. It was great chatting with you.

Rita: Yeah. Thank you so much. It’s been such a pleasure.

Video with captions

Transcript

Lazou: Our guest today is June Chua. June loves to tell stories in a myriad of ways. She’s an award-winning filmmaker with more than 20 years experience in journalism, writing, editing, broadcasting, and communications. She also helps artists with their proposals and grants. She’s now developing a creative non-fiction project: a collection of poems and stories.

In 2015, she decided to resign from her life in Canada, selling her things, giving away books, and moving to Berlin alone. It would mark a second migration. Her family moved from Malaysia to Canada in the seventies. June, thank you so much for being here with me today.

June: I’m so grateful and happy to be here. Thank you for having me.

Lazou: So your family moved to Canada from Malaysia, and you grew up in several places in Alberta. What was that like for you growing up? Did you feel like you were part of the communities around you?

June: I love this question because I come from Alberta, which I’ve often told people is considered the Texas of Canada, and you can take that many ways. It’s very right wing, it’s cowboys and oil. However, we did end up in a small town called Oyen out on the ball prairie in a trailer park. I can’t think of a more North American experience.

We had no idea actually when we moved there, what it was supposed to be. We didn’t have stereotypes in our heads, at least I didn’t, I was quite young. And Oyen being less than a thousand people with the only other Asian family running a Chinese restaurant we were definitely people who stood out.

But I have to say it was a truly magical experience. And I’ve found it interesting that people from big cities are often astonished that I say that. But maybe this is a simpler time, if I can call it that in like the late seventies because people were welcoming. They smiled at us. My father took a job out there as a gas and pipeline engineer. It was the first job he was given, and they said to him you’ll need to live out in this little tiny town for six or seven months. So he said, doesn’t matter, we have almost nothing. We each had two pieces of luggage, so we just moved out there. He had a coworker named Harvey whose wife Ruby was very kind.

And she also had three kids. I think it was only our second day there, we heard a knock on the door and she had baked a pie for us. I know this is sounding like I made it up, but I did not make this up. Harvey and Ruby and their three kids they were wonderful. And I had my first Halloween there, our first Halloween ever.

And I think there can be nothing more magical for a small child than to think that people would give you candy for free. we couldn’t believe it. It was just like, what is this? My parents got to know people in town and one of these teenage girls said, I’ll take your girls out trick or treating.

So she took us trick or treating around this wonderful town where we got free candy and we would even trick or treat at the little hospital. Or maybe it was a clinic, I can’t remember. But the clinic gave us like bandages. And then we would trick or treat at the local max Milk or seven 11 or whatever you wanna call it at that time.

And, of course they gave us lollipops and stuff. It was absolutely fantastic. And the kids, even in this school, were very kind. And I have to say, when we’ve moved into the big city, which is Calgary, and Calgary at the time might’ve had 700,000 people. I think it’s now 1.3 million.

But Calgary was rough. You always think, oh, a bigger city. There’s multiracial kids and, there were more kids that looked like me or looked South Asian or whatever. But for the first time in my life, and I hate saying this word, I was called a chink. And it’s taken me most of my life to be able to say that word without feeling the sting.

It was literally a kid who refused to play with me and told my white friend, I don’t play with chinks,

Lazou: Wow,

June: And when you’re eight or nine years old that incident stayed with me all through my life. I know that your audience out there, whoever they are, have probably had that singular experience where they were alienated and othered in such a brutal manner, especially as a child where you just sitting there going, I don’t understand what he’s saying.

Why? Why is this a problem? You don’t even know me.

Lazou: Yeah.

June: So I don’t think of large cities as these wonderful multiracial places. I actually don’t. I sometimes feel that they can be places that are even more alienating because people stick together. If you’re in a small town, you have to get along with everyone. There’s no choice. So I grew up in Calgary and it’s still weirdly my hometown. It’s the town of the biggest rodeo on earth, the Calgary stampede. Which is also a strange thing to grow up with as a little Asian girl. Because every year we dress up as cowboys and we have a parade.

I remember that parade. I had a little pink cowboy hat. My mom dressed us up in Western gear, mostly like Western shirt and jeans. And then we would watch the parade, which starts the Calgary Stampede every year in July. And then afterwards we would go for Dimm Sum in Chinatown.

Lazou: It’s awesome.

June: That encapsulate the entire Albertan experience for me how strange it is to say all these things in one paragraph,

Lazou: yeah.

June: So I would say that it was harsher in the big city but eventually I got friends and I felt all right.

When you look back from this point of view from years later, I realized that I purposely chose to befriend white people. It’s like I felt that protected me.

That’s something that has taken me years to understand and years to undo, to be honest I have to be honest to all my Asian brothers and sisters out there that I purposely avoided befriending other Asian people. Although I would say by the time I hit high school, I had friends who were, Chinese Korean, you know by high school it was all right. But still, I think I’ve definitely struggled with that idea that if I’m with a white person, I’ll be safe.

Lazou: Yeah, so was it like you felt that if you were with other Asian kids, you would be stereotyped as one of those kids, whereas if you were with mostly white people, you would be accepted as one of the white kids, even though you’re not quite white. Was that kind of the thinking? Yeah.

June: I think you hit the nail on the head. It’s oh, I’m not one of those Asians. I’m one of you. I understand you.

I eat white bread.

Also when I say safe, if you’re walking down the street with a white person, I felt and I still feel that, to tell you the truth, I felt that no one would bother me.

Lazou: yeah.

June: And unfortunately it’s true to this day that if you’re a couple of Asian or p o c people, you can be a target

Lazou: Yeah.

June: It’s terrible when I think about it now, so many decades later that this is still the case. Yeah, I was white adjacent.

Lazou: Yeah. So the poem that we just played, that you wrote in your poem, you have a few items that really punch me in the guts because they would’ve been on my list too as a teenager. The eyes, the nose, being tall and svelte, all those Eurocentric beauty standards.

How has your perception of beauty and your physical attractiveness changed over the years?

June: man. Do you have another couple of hours? Yes, it has changed. I didn’t feel attractive for years. I thought my nose was too flat. As you can tell, I wanted a bridge for my nose I didn’t have those big eyes.

And, my skin was a bit dark. I didn’t have that fair hair, all that stuff. But I have to say, it goes through levels because as I got to university, I understood that oh, I’m attracted to some people and people find me attractive and they want to go out with me.

And I thought, okay, then obviously whatever standard of beauty I had ebbed away in university. In my twenties, I was still thirsty for more representation. There wasn’t enough Asians anywhere and especially females, and I wanted to have more of them. But there were very few.

Sandra Oh in the 1990s started her career in Canada, and I followed her trajectory because we both grew up in Canada around the same time, I am not obviously as famous as she is, but I consider her like a contemporary in that sense.

Lazou: Yeah.

June: And so she was the one I hung onto like 20 years, I swear, because it’s while she can appear on camera, she has monoliths and a round face.

And of course on different shows, people find her attractive, So I hung onto her for a while and then I think.

What really worked for me was sometime in the early two thousands, I took up flamenco dancing and -surprise, I took flamenco dancing. And that did something for me that I don’t think therapy or even talking it out could have done for me, which was I put myself, I’m not a very good dancer, by the way. But I took it because I thought, Hey, that is the first female dance form that I’ve seen where the woman does not have to be 80 pounds, where she doesn’t have to be so light on her feet. In fact, you are required to be heavy. I like that you stomp your feet and that you’re of the earth. That’s what I liked about that dance, and I hadn’t seen much of that growing up. It was just ballet and goodness of, waltz’s and stuff, the old stuff. And so I decided to take it just for the feeling of like heaviness to be rooted.

I took it for six years and I loved it. I am a terrible flamenco dancer. However, my teacher, this wonderful woman in Toronto said, flamenco dancing is not about perfection. It’s not about some strange idea of looking beautiful. Flamenco dancing is emotion. She says, I’ve seen wonderful flamenco dancers where everything just looked gorgeous, but they didn’t have emotion.

And I have seen flamenco dancers where if you really look at the way they dance, it’s not perfect, but they do it with such emotion. That’s what flamenco was about. You are there in the moment and you put everything into it. And it could be rage, it could be sadness, it could be happiness, but be there.

And I think that on its own, made me understand that my body wasn’t about other people looking at me. It was me moving my body in a powerful way. Understanding that my body is here for me. I get to move from A to B with my body. I get to wake up in the morning, I get to walk, I get to get on airplanes. I get to hug people.

And so that gave me such an inner sense of the beauty of the body.

I wanna also tell people that I struggled a lot in my teenage years with weight, with dieting. And this may sound familiar to a lot of people. And I still feel the struggle to this day about my body. However, I am very conscious of the fact that I did flamenco.

That incredible sense of being rooted somewhere to the earth and being powerful has a lot to do with inner beauty. . And so now as I get older, I see that my body has changed and I’m going through another sort of, oh, my body is not as svelte as it was before and I can’t eat so much chocolate But I try to remind myself, how do I feel? Do I feel still strong in my body? And most of the time, yes, not all of the time, but most that’s where I’m at.

Lazou: Yeah. It’s definitely a struggle that a lot of us, especially women have faced in terms of trying to fit into that European beauty standard.

I struggle with my weight too, but I like chocolate too much. I was like, screw it. I’m giving up.

June: I’m with you, Sherry. I did a lot of dieting in my teens, and then at a certain point in my twenties, I was just like, I think this body is pretty good. It seems to be attractive to me and other people. And I love food so much that I cannot really give up on anything like chocolate or I have to say bacon is my failing.

And potato chips, I cannot, I have to just eat them. I cannot put them in my house,

Lazou: you’re Canadian, so you have to eat bacon, don’t you?

June: I do actually. It’s my patriotic duty to love bacon so much. People can’t believe it. I actually eat bacon three times a week. I know. It’s I love it, but I also eat oatmeal.

Lazou: Now your list also speaks to cultural clashes, whether it’s related to food, gender roles, career choices, or things that were not worth spending money on. Do you wanna elaborate on the gap between what you felt you needed in order to fit in and what your family valued at the time?

’cause it seemed like a lot of those things you felt like if you had those, you would be able to fit in better.

June: Yeah. This topic of belonging is so big that it’s almost difficult to encapsulate. The desire of any human being is to belong somehow.

As an immigrant child who didn’t look like everyone else, I didn’t feel like I belonged in my early years in Canadian society or in school, let’s just say.

And my family also had different values that I didn’t understand, so therefore I didn’t belong to my family either. I now can look on it as an adult and go, wow, those two are very painful. I would feel like I needed to belong, like all the kids in school, because in my family it was very strict.

And this may be a familiar story. The slogan of our family, if you could think of one, was get good grades, work hard. And eventually you will marry, buy a house, have children. That was the trajectory that you just knew. And I understand that is something that my parents felt was needed for survival, just pure survival.

And as an adult, I can see fully that they were scared. They have three little girls and what they wanted was for us to be secure and what else? But to become one of five professions. Is it doctor, lawyer, dentist? What are the other two? Engineer? And there’s a fifth maybe pharmacist,

Lazou: Accountant.

June: accountant. right. I joke about this with a lot of friends who didn’t come from Asian families or immigrant values, and they thought that’s not true. I said, you don’t understand. When I look at the people, like my parents’ friends and their children, guess what they became they really did. A lot of them became one of those groupings.

So I really needed, I used the word Mr. Miyagi. Mr. Miyagi stands for so much in that poem, which is a role model, someone to mentor me and to reconnect me maybe to something from my own culture that I could be proud of. Which, at the time I know my parents didn’t have time. They were working too hard. So that’s not something I can fault my parents for at this time. But it is something that years later all of us have to deal with this sort of lack this gap.

You say it felt like a chasm, like a huge canyon between the fact that I didn’t see myself as any of those five professions at all. I was so far away from that internally, and then also that I wanted to be Sandra Oh I just admired her from afar. Because I was like, wow, at the age of 19, she got her first starring role in a Canadian biopic of a Chinese Canadian poet, which is actually quite major when you think about the 1990s that time.

Mr. Miyagi stands for so much, I needed that type of person to guide me and to tell me that I had choices. And when you’re growing up in what I would deem the Texas of Canada in a immigrant family when there’s no internet by the way, and you can only watch so many TV channels that have white people on them, then what are my choices?

It’s so limiting

Lazou: Yeah. One thing that came from that poem when I was reading it, was it seemed like you felt you lacked choices, that you didn’t have agency. So at what point did you finally feel empowered to be yourself and pursue the careers that you wanted?

June: That is a very good question because having agency has taken me years. I think I had a tiny amount of agency in high school when I took a drama class. I just thought, you know what?

Life isn’t just about chemistry, math, biology, and whatever else I had to take. I looked at this and went, I’m gonna take drama class because no one can stop me. It was one of my credits. So I did, and I am eternally happy that I found this class where a man named Agrell pushed us.

Everyone can talk about a very good teacher in their life. Mine was the drama teacher. He basically took us through a journey through world history.

And if you took his class for three years, 15, 16, 17 years old, he told you that, if you’re an artist in the world, you have to know what’s happening in the world.

He pushed us a lot as high schoolers to understand the world.

He infused in us critical thinking. He would say, what did you watch on the news last night? This is drama class. We’re just like, oh, we watched people were starving somewhere. He goes, and do you think that’s your fault? I said we’re not sure. What answer do you want? And he just said, think about it.

What caused the starvation? And really, he pushed us to think about the world of politics and economics and how does that affect people? And then he introduced us to the idea that, when you write plays, you’re not just a person in a cave writing a play.

You’re part of the world.

So we’re gonna study this play. Now, we’re gonna research what was happening at the time that the playwright wrote this? Study everything, dig it up. If we studied a play, we had to study everything about the playwright and the time that he did the play, all the social things that were happening, politics, whatever that would affect how the play was written and why the playwright wrote it.

He gave us a good grounding on world politics, history, society, and how plays are done or produced, how the playwright goes about doing these things. And I think that gave me an opening into, oh, the arts isn’t just some endpoint, it’s a whole world, a universe of creation. And if you’re in the world, you can be an artist.

As a high school student, it opened me up to world history in a way that made me understand that there’s a lot of things happening out there. It sounds so general, but it was bigger than the five choices of careers that were open to me.

Lazou: Yeah.

June: And I think that that gave me some agency to pick journalism as a career, which at the time, I have to say I had no one in my life did anything that different. I look at my cousins and my aunts and uncles. I have virtually no one to follow. At the time, I just thought I can call myself a journalist and that’s just a little bit different and I get to write, or I get to do something that is not part of those five professions.

Doctoral lawyer, dentist engineer, accountant. That was my first introduction to having some agency, but actual agency, I would say arrived later in life. Later in my journalism career.

Lazou: So Let’s talk a little bit about your career in journalism. What was that like to navigate as an Asian woman at the time in Canada?

June: I find it strange when I hear the word career because sometimes when I look back it looks like I created this, but a lot of times it was just like, I think I’ll become a journalist and see where I go with that. And I enjoyed it. The difficulty in the nineties in Canada was that there were so few of us and we were often seen as special hires. This is a big problem because you need to have people of different backgrounds in a profession, but the people hiring are all the same kind of people, white. So they had to institute programs to make sure they hired people of different backgrounds. And then the problem is you enter these white newsrooms and they just look at you as if, oh, you’re special. how could you be good?

Lazou: Yeah.

June: No one questioned me that way, but you could sense it and feel it. There were only a few of us, and you could tell that they were very wary of us. The people who’d been in the news for, let’s say more than 10 years, you could sense it.

Just the way they looked at you, it’s like, oh, another one. I wonder how she’ll do. The difficulty when there’s only maybe three people of color in a newsroom, let’s just say, and one person isn’t very good, then suddenly all people of color get painted with the same brush, which is awful. Like I, I don’t even have words to say that. Whereas I encountered in newsrooms, people who were of white European backgrounds who were not doing very much, and some of them were rather inept, but they never got fired. They were part of a large group of people. So no one ever said, oh, all those white people, they must be inept because these five, other people are inept.

It’s just unfair on so many circumstances. And that’s what happened. They would quietly say to me, oh, you’re doing great. And I could tell that they were relieved because, I don’t know, some other special hire didn’t do so great. It is really difficult because I busted my ass for the first five years of journalism like you wouldn’t believe. And I still felt I was going nowhere because it’s always been competitive profession, even more so now. But in the 1990s it was like I did double the stories of some of the men who’d been there for 15, 20 years and still they weren’t gonna give me a full-time job.

Lazou: Wow.

June: And, you know, this is the 1990s, this is not 2020 where we have a lot of other things going on in media. And I was people pleasing a lot too. I was trying to, again, fit in, be happy with everything and bust my butt doing so many stories and I burnt out. I actually burnt out in my twenties, which is not unusual these days to burn out in your twenties.

But I burnt out

Lazou: Yeah.

June: and I took my own sabbatical when I was 26. I went to France.

Lazou: Nice.

June: So I always say to people, understand why you are working and protect yourself.

A lot of times it’s not because you work hard and you’re good, it’s because of other circumstances. And so you have to protect yourself, your health, your wellbeing. That’s number one.

Lazou: Yeah. There’s this double standard when you’re a minority and they consider you a minority hire, it’s like, when you’re good it’s oh we’re all good. So of course you have to be good. When you do well, they don’t go and say, oh, all the bipoc hires must be good.

No, that doesn’t happen. It only happens in the other direction.

June: Oh, so true. That is so true. That’s what’s so frustrating.

Yes. Yes. I always try to counter that type of talk with You know what? Being part of this great world and being someone of a different background than all the other white people, I am also allowed to be a failure. How about that?

Lazou: Yeah.

June: Can’t you see me as a whole person?

Lazou: Yeah.

June: That’s what makes me wanna scream. It’s just like I can be a bad person. I can be also a good person. I can also fail and also fail at a lot of things in a gigantic way, but I’m allowed to fail. But this is the difficulty the whole model minority image of, smiling and working hard and all that stuff is just, frankly, I’m just tired.

Lazou: yeah.

June: I just try to be direct. Now, I don’t wanna be a smiley Yes person, as you can tell I’m not. I have tried all my life not to be, but there have been many times at work where I’ve had to be, and that’s what I don’t like Sherry, is that I just thought, I don’t belong at work either.

I don’t belong here with these smiley people nodding their heads. That was very unpleasant for me too. And so I guess I’m still finding myself.

Lazou: I think that’s a lifelong journey for all of us.

June: Totally. Totally.

Lazou: it’s a lot of pressure when you’re a minority in any setting,

You have this burden of representing your people. It’s like, I am not all the people. In fact, I’m probably a poor example of my people in many respects. Don’t look at me for that.

June: Hallelujah. I totally, that’s exactly what I would say too.

Lazou: So how did you branch out from journalism into other fields?

June: I think that Documentary filmmaking is linked to journalism, and I wouldn’t say I branched out as much as I saw a story that I felt I needed to follow. And by the mid two thousands, I’d already spent, I don’t know, more than a decade in journalism at that point.

And I’d already gone into like online journalism, one of the early people at the time, and I thought, okay, this is fun, but really I would really like to do more. I only did a few documentaries. The first one was called "Twin Trek" and it fell into my lap. It was a story about Bengali Norwegian twin brothers from Canada who go to a family reunion in northern Norway and uncover a secret.

That’s my elevator pitch. And it fell into my lap at a time when I was really looking for a challenge actually. And so I had to buy a mini DV camera, figure out how to shoot. I didn’t know how to shoot a camera at that time. It seems so easy now with all the technology, but at the time, no.

I bought the camera kit on my own. Then I taught my partner at the time to shoot a camera, or rather, I asked a fellow filmmaker who happened to be a slightly older Chinese Canadian cameraman. He said, listen do you need help? I said do you have one day where you can just teach us camera tricks?

He said, sure. Just buy me dinner. I’m like, no problem. Basically, he said to us, your friend is this switch. It was the automatic switch. Because when you’re running around trying to shoot a doc and things are unfolding, you can’t do white balance or focus. You just press automatic June.

And the other thing is always have sound. Make sure your sound is running. You can always try to do something with the pictures if something goes wrong, you can somehow scrape by. But if there’s no audio of a key moment, you’re screwed. So it’s like audio. Yes, audio. But yeah, that’s how I fell into documentary filmmaking.

And on my first try at Hot Docs, the largest documentary festival in North America. I won my pitch.

I won my pitch.

Lazou: Awesome.

June: And I have to say, it is also thanks to a wonderful African American filmmaker called Marco Williams, who happened to be standing by the food table with me at a party at Hot Docs. And he looked just as uncomfortable as I did, although he has a lot more experience than me. I was a newbie I was just standing there and I looked at him, I said, Hey are you a filmmaker here? Whatcha doing here? And he just started talking to me. Then I told him that I was trying to pitch my first ever doc, and he goes, I can help you.

So we worked on my oral pitch. you know, I have to Sit there in front of a commissioning editor and tell them your story. so we worked on it over a period of 10, 15 minutes and yeah, I won the pitch competition for that specific pitch prize.

Lazou: Amazing.

June: that got me rolling.

Lazou: Awesome.

June: Yeah that’s how that happened. But a lot of times it’s me feeling a little bit bored and trying to find new ways of doing other things. That’s how I fell into a few things here and there, I was seeking.

Lazou: Yeah. And you had not one, but several amazing careers in multiple different creative fields. So I wanted to give you the opportunity to tell us about some of the highlights, your favorite moments in various roles that you have played over the years.

June: I think she, it’s really difficult to be beating my chest. I’m not used to it, believe it or not.

Lazou: It doesn’t have to be something that you feel like deserve international acclaim, but it can be something that you were proud of. What was a piece in journalism that you worked on that you were really proud of, or any other project that you were proud of.

That’s all that matters.

June: Thank you. It’s a lovely question to ask because then it makes me understand what I’ve done, and I don’t pause many times to think about it.

There is a few things I would say I’m most proud of. I worked in the town of Ottawa, which is the capital of Canada, as a TV journalist, I was actually the first journalist ever allowed to follow the SWAT team in Ottawa.

So we did a two week follow along and it sounds so quaint now, but at the time they did not allow TV journalists along. And so I had a first, let’s just say, and we did this huge long TV doc about the, they call them the tactical unit, they don’t call themselves swat, but I hung around these guys.

It was the most intense, dare I say, fun follow along to understand how they work.

The other thing is Twin Trek", the first independent doc I did did not end up at Hot Docs or at, the Berlinale or at any major festival in the world. It did not end up at any medium-sized festival either. I spent a whole year completely frustrated, like a lot of filmmakers, like, why wouldn’t anyone watch my film? But there was one year, it just seemed, it felt like it was the year for my film. It ended up being shown in this special cultural festival in northern Norway.